By Chris Gray Knight Ridder Newspapers (KRT) AUSTIN, Texas _ Marlen Whitley remembers looking around his entering 1998 class at the University of Texas law school with frustration. Of the 468 first-year students, eight were African American _ less than 2 percent. And those numbers were double from the year before, when only four blacks enrolled at the state’s premier law school. “It’s happening all over again,” Whitley told his parents, products of segregated schools in Arkansas. “It was like we had come full circle.” Whitley’s experience, as one of the first minority students to enroll after a court threw out affirmative action at Texas universities, may become commonplace on campuses across America. After years of letting lower courts waffle over the legality of racial preferences in college admissions, the Supreme Court is about to weigh in _ and officials at the University of Texas warn the results could once again dramatically alter the complexion of the student body. The University of Texas School of Law, once a bastion of white Texan privilege, had been using an admissions grid policy that included race as a factor. This system brought the school’s minority enrollment to nearly 20 percent in the early 1990s. Then in 1996, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, in New Orleans, ended affirmative action at public universities in Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi in a case known as Hopwood v. Texas. “We saw a marked decrease in our minority students,” said Monica Ingram, assistant dean of admissions at the law school. If the Supreme Court takes a similar stance, “our situation could become the reality.” The Hopwood case started when white students, including Cheryl Hopwood, sued the law school in 1992. Because the school considered race in its admissions, minority students with lower grades and test scores were being admitted over their white counterparts, they contended. To defend itself, the university cited the 1978 Bakke decision, which allowed race to be used in admissions to maintain diverse enrollment or remedy past discrimination. The university felt confident in its argument, particularly because the school had faced repeated court orders to desegregate, said Douglas Laycock, a law professor who helped defend the university in the Hopwood case. For example, in a landmark 1950 ruling, the Supreme Court forced the University of Texas to admit a black applicant, Heman Sweatt, to the law school. Even into the 1970s, the federal Office of Civil Rights cited the university for failing to increase minority enrollment; affirmative-action programs were put in place in reaction to those events, Laycock said. “It’s one of history’s ironies that both (Sweatt and Hopwood) happened here,” he said. The Fifth Circuit’s ruling, throwing out the program to increase minority enrollment, hit the University of Texas hard, both in its undergraduate and graduate schools. Minority applications dropped, as the school’s reputation as an inhospitable place for blacks and Hispanics was resurrected. In 1997, only 190 black students were in the UT Austin freshman class _ about 3 percent. Hispanic enrollment also declined slightly, to 13 percent. Numbers at the law school were worse: Only four blacks and 26 Hispanics enrolled. Concerned, the Texas Legislature enacted a law that required state universities to automatically accept all students ranked in the top 10 percent of their high schools, regardless of test scores. Because many public high schools in Texas are predominantly black or Hispanic, legislators figured the plan would increase minority enrollment at the universities. But they were wrong, said Bruce Walker, director of admissions for UT Austin. “Simply making students eligible to attend is not sufficient,” he said, adding that the university had to work on changing its reputation in minority communities. “It just doesn’t work that way. That first year, it made almost no difference in enrollment.” Forbidden to offer scholarships by race, the university started giving money to students from selected high schools _ the ones that happen to have mostly black or Hispanic students. There are now 74 “Longhorn Opportunity” schools that administrators target with recruitment visits, assigned admissions counselors and scholarships. With this aggressive outreach, undergraduate minority enrollment is back up to pre-Hopwood figures. Admissions director Walker is the first to admit the numbers are not great: Last fall’s freshman class included 272 African American students, 3.4 percent of the 7,935 total. Hispanics made up 14.3 percent of the class, with 1,138 students. Because the Hopwood decision does not rule out geographic preference, the law school now reserves 15 seats for students graduating from five historically underrepresented colleges in a largely Hispanic area of the state. It has also added questions about parents’ educational levels and languages spoken at home and an optional essay on “economic, social or personal disadvantage” to its application. The programs and the questions have helped, and minority enrollment at the law school is increasing, Ingram said. This year’s class of 543 had 21 black students, 43 Hispanic students. But Laycock, the law professor who helped defend the university in the original Hopwood case, says the additions are merely the university’s attempt to find a thinly disguised “proxy” for race. Because they ignore test scores, such proxies often lower academic standards far more than affirmative action ever did, he said. “The system wants us to have some admissions criteria that isn’t race, but there is no way to get more minority students in without considering race,” he said. Now an Austin lawyer, Whitley, 27, hopes that the Supreme Court will avoid making a decision that sets back educational opportunities for the next generation of African American students that will include his newborn son. “When I entered, I was one of eight. Sweatt was one of six,” Whitley said. “Fifty years and we had come full circle… . I hope in 18 years that we can look back at this as a historic moment that he can’t relate to.” ___ ‘copy 2003, The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit Philadelphia Online, the Inquirer’s World Wide Web site, at http://www.philly.com/ Distributed by Knight Ridder/Tribune Information Services.

Latest Stories

- BG24 Newscast

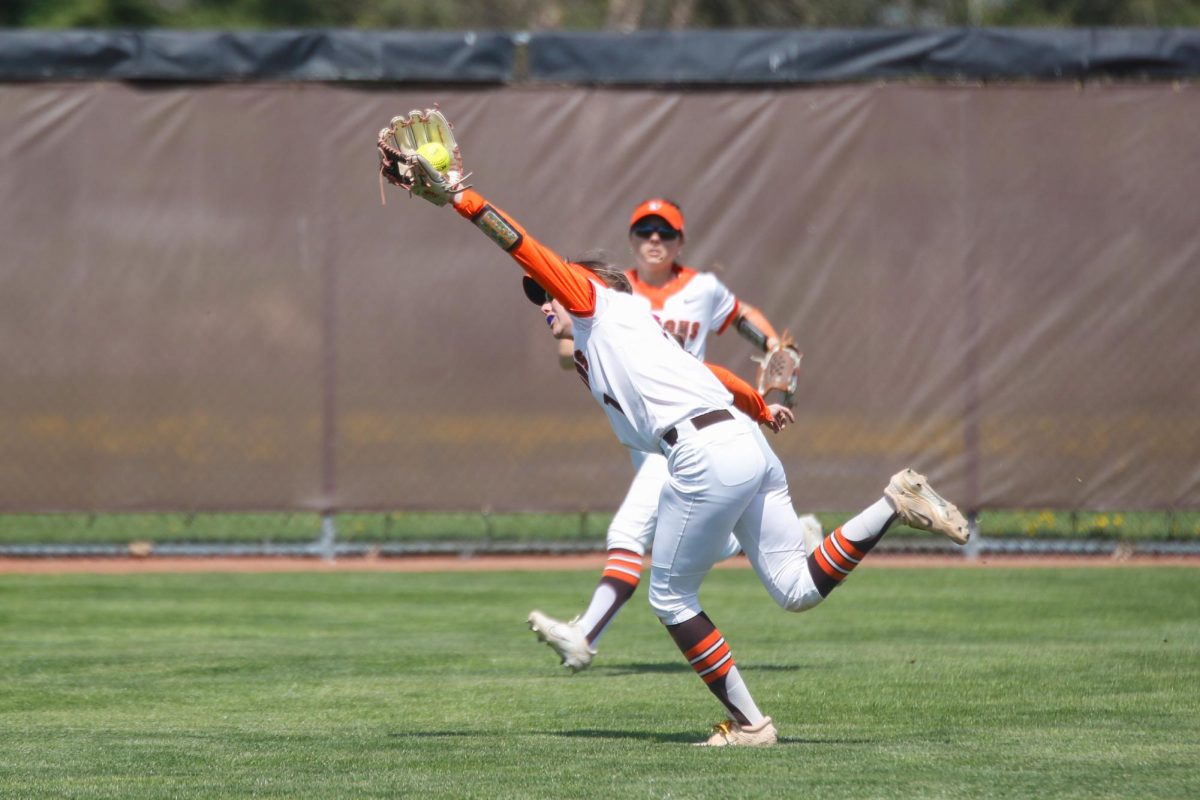

- BGSU baseball vs Ohio preview: Falcons’ storybook season continues with homestand against Bobcats

- From the Golden State with a golden opportunity- Justin Eklund makes his way to BGSU

- 74% percent of women in the U.S. are embracing makeup: What's behind the trend?

- Brady Pavernik leads way as Falcons finish sixth in the Highland Meadows intercollegiate tournament