The athletes have packed up. Olympic banners are coming down.

The challenge is just beginning.

It’s a realization that’s just s tarting to hit the Olympic hosts: The venues and facilities they struggled so hard to build could create even greater problems after the games.

The chief fear — especially after Athens’ budget- busting Olympics — is expensive idleness. World-class sports centers ring up serious maintenance bills. Finding relevant and revenue-producing roles for the arenas is the long-term quest of any former Olympic city.

In Athens, however, there’s an added complication. Olympic planners dedicated so much effort to overcome delays, there was no time to think about the future. There’s now more than $3 billion in new or refurbished venues begging for attention.

“There are ideas. Some plans are being studied. But there is no definite solution,” said Christos Hadjiemmanuel, head of Olympic Properties, a state company created as a temporary caretaker for the venues and other sites.

Time is truly money in the post-Olympic landscape.

A University of Thessaly study commissioned by the Greek government predicted it will take $100 million a year for the upkeep of the more than one dozen Olympic sites, including the main stadium complex. Add this to an overall price tag expected to reach $12 billion — nearly all of it from public funds.

Greek taxpayers are already expecting to be hit hard by the state. Even before Sunday’s closing ceremony, the hunt was on for ways to lighten the post-games’ costs.

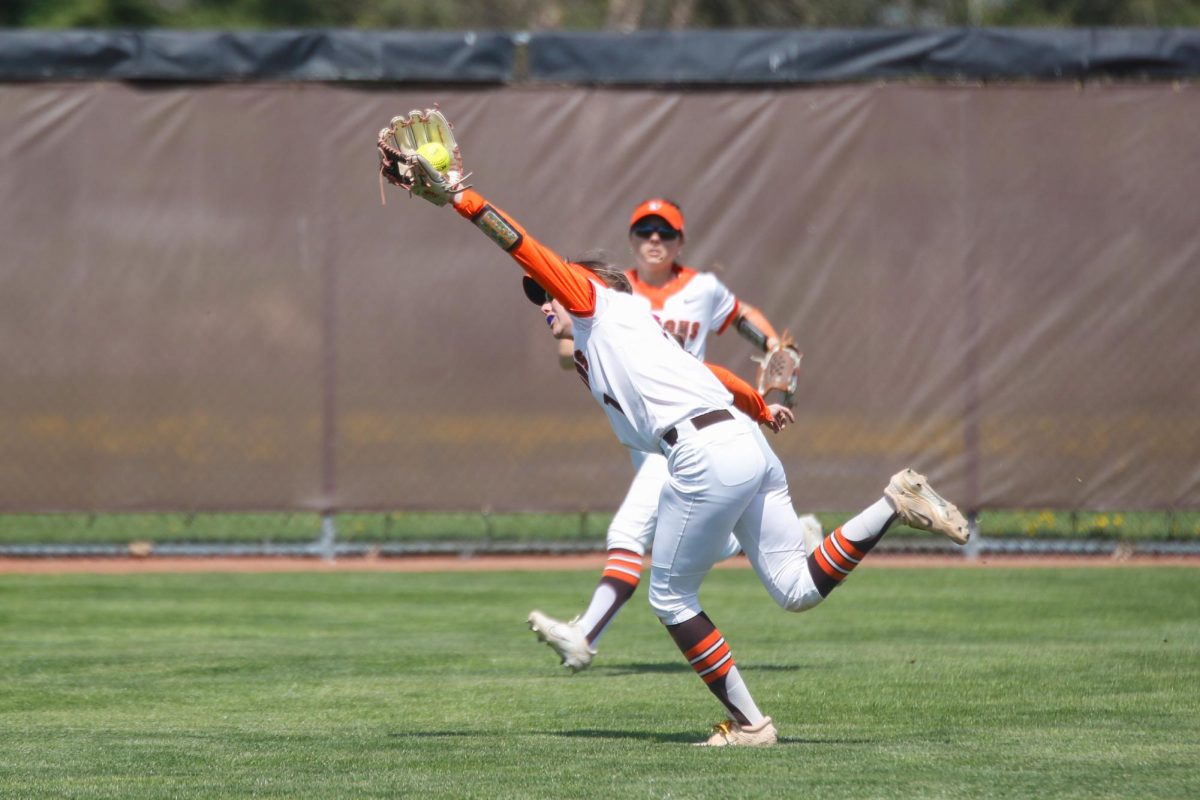

Ideas — some possibly floated by the government — filled the Greek media. Among them: closing the venue for badminton and the modern pentathlon; seeking private buyers for some sites; and digging up part of a sports complex on attractive seaside property that was formerly the city’s airport. There would probably be little local outcry. The fields were used for sports with few followers in Greece, including softball, baseball and field hockey.

The only clear plans so far involve converting the Olympic Village into apartments for low-income Greek workers; turning the media and broadcast centers into conference halls; and

modifying media housing for a range of uses such as Education Ministry offices, a shopping mall and a police training academy.

There’s already talk of mounting Greek bids for the European soccer championships or other high-profile sports competitions.

“Our city has been changed for the better by the games,” Athens Mayor Dora Bakoyianni said. “We must now decide how to keep the momentum.”

Athens has new rail links, highways and revamped public spaces that planners hope rid the city of its shabby and chaotic reputation. Police have been trained to provide security on a major scale, which officials believe could help attract conventions and other sports festivals.

This is what the International Olympic Committee calls “the legacy.”

It’s the catchall phrase for projects, transportation improvements and the general facelift for Olympic cities. But there’s a caveat: The IOC has increasingly warned hosts of making costly venues that have little draw after the games.

“These are the white elephants that the IOC talks about,” said Robert Baade, a professor at Lake Forest College outside Chicago who studies sports’ mega-events. “There are plenty of examples.”

The highly praised Sydney Games left some pricey baggage.

The privately run SuperDome went into receivership this year. The $420,000 mountain bike track was closed because of a lack of riders. The equestrian center needs more than $900,000 a year in subsidies to stay afloat.

In July, Australian officials forecast it could take a decade to break even from the cost of staging the 2000 Olympics. Taxpayers, meanwhile, are paying about $32 million a year to prop up the underused venues.

Atlanta immediately converted the 85,000-seat Olympic stadium into the home field for the Braves. Smaller venues had a less fortunate afterlife. The shooting venue was closed. So was the beach volleyball arena, which is now used for wedding receptions and may be part of a future senior center.

The 2002 winter host, Salt Lake City, fared better than most: a $76 million endowment left behind by the organizing committee for a winter sports complex. A $1.6 million operating deficit, however, forced cutbacks and layoffs earlier this year.

Montreal, host of the 1976 Summer Games, was stuck with a public debt worth billions in today’s dollars.

The ultimate shakeout for many cities could resemble Mexico City’s. The sombrero-shaped Olympic stadium from 36 years ago is still in good shape as a venue for pro soccer. It contrasts sharply with the facilities that could not find their footing after the games. The indoor Olympic pool has the feel of an abandoned factory. Graffiti covers the modernist sculptures created for the games.

“This whole idea of a bright, shiny Olympic legacy is a terrible sham,” said Anita Beaty, an activist who fought Atlanta officials over plans to restrict movement of the homeless and others. “There are dark sides.”

That is what Athens is trying desperately to avoid after silencing critics and pulling off well-run games.

The soccer stadiums, including the 75,000-seat Olympic centerpiece, will be used by Greek soccer clubs, although only a few thousand fans generally turn out for many matches.

Basketball teams will take up residence in some of the halls. Sailing, a popular pastime in Greece, probably will benefit from the new marina facilities.

It’s the smaller sites that are the biggest worries. Greece, with about 11 million people, might not have the sports base to sustain venues for shooting or indoor cycle racing.

Greece’s deputy finance minister, Petros Doukas, said the government is seeking to shift a “big chunk” of Olympic venue management into private hands. The reason is as obvious as red ink.

“There just isn’t much public money left after the games,” he said.

Some Greeks have opposed widespread selloffs of the venues, saying they should remain a public resource. But others acknowledge the debt-smothered government can’t handle it alone.

“Privatizing the venues or charging a price for their use is preferable to their being given free-access status yet left to rust,” an editorial in the Kathimerini newspaper said.

After a meeting last week on the future of the Olympic sites, the government spokesman summed up the state of the blueprint.

“We’re open to all ideas,” Theodoros Roussopoulos said. “It’s an open book.”