University administrators are determining what academic courses need to be eliminated or revised after 18 percent of courses were shown to have low enrollment according to state law.

A report submitted to the Ohio Department of Higher Education by the University Jan. 31 said 581 courses had failed to reach “20 percent above BGSU’s threshold for the course over two or more semesters,” the definition of low enrollment set in Ohio House Bill 64.

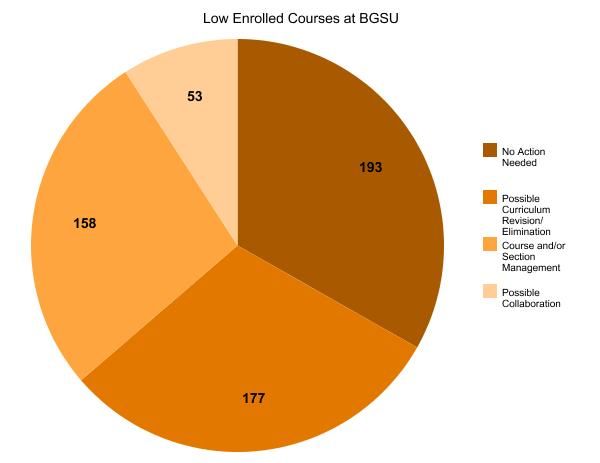

The courses were categorized into four avenues of action: no action needed, possible curriculum revision or elimination, course or section management and possible collaboration. The report was distributed to chairs and directors of various departments and programs, who then consulted with faculty teaching low enrolled courses to choose which category their course fell into, said Julie Matuga, associate vice provost for institutional effectiveness and leader of the team that analyzed the course data.

The courses most likely to be low enrolled are upper level ones aimed at juniors and seniors, Provost Rodney Rogers said.

“The typical under-enrolled (course) is going to be some course that’s related to some specialization that’s one of three specializations in a particular major. And there might be only six people (pursuing that specialization),” John Fischer, vice provost for Academic Affairs, said.

These upper level classes are also more likely to be consolidated or eliminated, which could affect those on track to graduate in smaller programs or specializations.

There will be an emphasis on ensuring the student is not impacted, Matuga said.

“As a matter of fact, it may increase the availability of some courses and some avenues of completion,” she said, referencing online courses specifically.

New technology implemented to track credits has also given the administration insight into what courses need to be offered so students can graduate on time, Rogers said.

A majority of the low enrolled courses (33 percent) required no action because the education style of the class or the classroom space restricted enrollment.

“If it’s a very experimental course . . . 15 people in might be exactly what you want to do, because it will help the most students be successful,” Fischer said. “The state is not asking us to do away with all that, but it is asking us to defend it.”

The University’s Board of Trustees will decide what action to take concerning the low enrolled courses, according to HB 64. The Board approved the report at its Feb. 19 meeting.

Matuga said her team also looked for courses categorized incorrectly, such as practicums, experiential learning or independent studies mistakenly categorized as lectures.

Some courses had multiple low enrolled sections, indicating a need to consolidate sections or offer sections at a different time slot.

With the University in contract negotiations with its faculty, faculty may wonder what course consolidation, collaboration or elimination may mean for their jobs. Scott Piroth, communications officer for the Faculty Association, said while it is too early to know what the consequences will be, the loss of faculty jobs is one of the association’s main concerns.

“With the enrollment growth that we’re having, I don’t see that possibility at all, quite honestly,” Rogers said. From fall 2014 to fall 2015, total enrollment at the University increased 1.68 percent, according to the 15-day headcount comparison.

His prediction is that the action taken with the courses will help the University use existing faculty to deal with enrollment growth.

Another option is collaboration, both within the University and with outside institutions. Rogers said some similar courses are offered in two or more colleges within the University and could be consolidated into one course.

Piroth was hesitant about using this solution.

“There might be a good reason for why these courses are in different colleges,” he said. “They’re more different in the way that they’re taught than they may look like just from the descriptions.”

The University may also collaborate with other four-year institutions in order to offer some courses to students, as it does with the University of Toledo for its nursing program and Masters of Public Health.

Rogers said collaboration on courses “may not be to the level of (the nursing program).” He said it would look more like sharing faculty between institutions to teach students in similar courses.

Collaboration on foreign language and cultural offerings was being discussed at the faculty and department level even before HB 64, Timothy Pogacar, chair of German, Russian and East Asian Languages, said.

He said faculty have talked with colleagues at other Ohio universities about working together on study abroad programs and the University now offers Italian as a distance learning course, which can be taken by students at other institutions.

“The objective is not to eliminate offerings, but to make more, better offerings,” he said.

Piroth saw possible limitations on faculty jobs.

“If (collaboration) were done on a large scale, that would be very problematic for faculty,” Piroth said. “I can’t imagine that the universities themselves … would want that to happen very often. After all, they’re in competition and they want to maintain a distinct identity.”

Administrators said enrollment is not the only way course performance is measured.

A more complete assessment of the student experience, Matuga said, is looking at curriculum, assessment practices, learning and engagement, among other factors.

“This is one piece of a larger pie,” Matuga said. “We’re always searching to improve the student experience here.”