Every time people decide to empty their bladder in public, they are potentially pissing their money away.

A citation for public urination can cost an offender between $25 and $150 and may incur a court fine of $90, said Matt Reger, city prosecutor. One hundred ninety-seven people were cited for publicly urinating in 2012.

“I feel peeing outside isn’t really hurting anything and it shouldn’t be that much of a price,” said senior William Porch Jr, who has admitted to urinating in the city before, but has never been caught.

While to some, public urination may seem harmless, the location may bring harm to property.

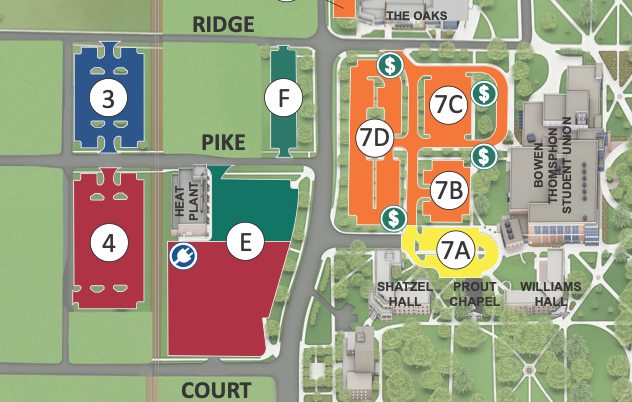

“People urinate all over, primarily anywhere from downtown to the University housing areas or rental properties,” Biller said. “Sometimes people urinate on sides of buildings, doorways, on a storefront. Quite a few urinate on cars, in parking lots — any place they can find to be somewhat secluded.”

For Porch, the trick to not getting caught is knowing how to stay out of the open.

In some cases, a full bladder isn’t the only thing that gets someone in trouble.

If the person is intoxicated when caught, other citations can accompany the public urination such as open container or underage under the influence, Biller said.

Depending on the officers’ discretion and the offenses, the person can be sent off with a $75 civil citation where they can just pay the fine, or take a criminal citation that would require a court appearance, he said.

Public urination is categorized under disorderly conduct and usually becomes a minor misdemeanor in court, where people can be fined anywhere between $25 and $150, Reger said.

Of the 197 citations, 109 were civil and 88 were criminal.

Porch believes the city is being “money hungry” by imposing these fines, but city officials don’t see it that way.

It was never pursued from an economic standpoint; the city is not trying to find one offense to make up for the gap between revenue and expenses in the budget, said John Fawcett, municipal administrator.

The law and fines are there to influence a change in behavior, Fawcett said.

Money that does get drained from offenders’ wallets from civil citations flows back into the city.

At $75 a citation, those 109 urinations flushed $8,175 to the city.

Those funds funnel into the civil infractions fund, which supports the city code enforcement division, said Brian Bushong, city finance director.

“It’s a relatively new fund, paying for part of salaries related to enforcement and office supplies,” Bushong said.

The fund totaled $27,197.19 and is paid into by citations such as disorderly conduct and code violation fees like leaving a trash can out on the street too long, he said.

It’s like how parking tickets pay for roads and the people who issue the tickets, Bushong said.

For criminal citations, depending on which code a person was cited under, the money can go to the city or the state after it goes through the local court system, Reger said.

The reason police may cite someone under state codes is because when an arrest is made, the cost to house the person in jail comes from county funds instead of city funds, Biller said.

During the course of the year, the municipal court sent $217,817 to the Wood County Auditor’s office to be dispersed accordingly, said Katherine Thomas, municipal clerk of court. Under the law, state money is sent to the county.

Money collected by the county from disorderly conduct such as public urination would be sent to the county general fund, where the commissioners would dispense it on their own discretion, said Deputy Auditor David Kuebeck.

The court also sent $423,565 in fees to the city, which went to the general fund, Bushong said. The general fund pays for salaries and purchases supplies and uniforms for city employees such as fire fighters and police.

While these 197 citations may be a lot of pee in the city, officials are not convinced to put a bathroom on every corner.

“People who are urinating in public can be coming from venues with restroom facilities and we’d like to think they’d use them,” Fawcett said.

Even though downtown venues have restrooms, Porch thinks public restrooms might solve the problem.

“Sometimes you don’t have to go to the bathroom until you’re already walking home,” Porch said.

The city hasn’t contemplated construction of a public restroom because the extra costs to maintain it and the liability of activities that might occur in the facilities, which can’t be policed, Fawcett said.

Vandalism of park restrooms is another reason to not construct facilities in the city, he said.

There are 16 restrooms between City, Simpson, Wintergarden, Carter and Conneaut parks and they can be costly to maintain and repair, said Michelle Grigore, director of Parks and Recreation.

Without patrols, vandalism would occur more often, but right now it happens during the night, Grigore said.

“People have set fires in the restrooms, spray graffiti, pull off soap dispensers and break mirrors,” she said.

The cost to maintain a restroom for an hour a day runs a total of $14,800 a year with staff and product fees, while a mess that takes two to three hours to clean can cost $28,000 a year, Grigore said.

Constructing new restrooms can cost between $100,000 and $120,000 with sewer and water hook-ups, she said.

The parks use portable restrooms, which cost $87 a month or $1,044 a year with a $60 tipping fee, Grigore said in an email.

While portable restrooms offer a cheaper option, Fawcett said the city has not explored that avenue because of location conflicts and extra policing that may be required.

“We won’t rule it out, but we won’t actively embrace it,” he said.

Porch believes money collected from the citations could go toward funding portable restrooms.

Despite what people like Porch may believe, Biller thinks it isn’t the city’s job to provide restrooms for the public.

“People should be responsible enough to take care of their personal hygiene,” Biller said. “It’s not the public’s responsibility to provide for that.”