Non-traditional artist and advocate

In the fine arts building on the campus of Bowling Green State University (BGSU) is a middle-aged woman who travels the halls, often using a rollator or power mobility chair. Elizabeth Meadows is a 53-year-old, disabled, non-traditional student who advocates for disability acceptance and mental health awareness.

While a large number of people may know who Meadows is as she rolls along the hallways of the 76-year-old Fine Arts Center, she did not achieve that level of acknowledgment without hardships and experiences that a student without a disability may not have.

“I’ve just been doing art for most of my life—art and music,” said Meadows. “I had to choose between art, music and English when I went to undergrad.”

Meadows has lived in Cleveland, Shaker Heights, Elyria, Oberlin and Huron, Ohio; Pittsburgh Pennsylvania; San Francisco, California; and now Bowling Green.

She earned her Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh in 1994. While attending the university, she obtained experience in a wide area of fields, ranging from ceramic sculpture to welding.

Following her graduation, she joined the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers where she learned how to arc weld.

“That was really interesting because females…really bad neighborhoods—and I’d just get out of my car and put my welding helmet on and walk in and they’d finally figure out ‘that’s a girl!’ and I was like ‘oh yeah, pretty much, thanks,’” said Meadows.

From there, she got married in California and had her first child. Eventually, Meadows went on to have a total of four children, ages 26, 23, 22 and 10 years old.

Before coming to BGSU, she gained experience working as the owner of a stone carving business, a mobile phone technician, a metal finisher for a sign company, a blacksmith’s assistant and even taught at a community college.

As she transitioned from working full-time to creating art, her artwork took on a wide range of different creations.

One piece of art she created were large flowers she would sell at a consignment gallery. Though the gallery is closing, she’s grateful the last flower she created for the shop was given to her mother by the gallery owner just recently.

While Meadows has a large amount of experience, she said when she came to Bowling Green, it didn’t seem to matter.

“When I came here, it was supposed to pretend like I wasn’t an artist and didn’t have all that experience, and that’s where some of the chaffing I believe was,” she said. “I’m definitely a non-traditional student because I come in with a child, and I have certain disabilities that have recently gotten worse.”

The child Meadows is referring to is her 10-year-old daughter who also has a disability. Meadows brought her daughter with her to BGSU because as a single mom, she said it was the best and safest option.

She also said it’s good for her daughter to have this experience.

“I think it’s good for her to be exposed to art and music and college students, especially burnt-out college students because they need a break sometimes,” said Meadows. “She likes to race students in the hallways.”

Throughout her time here at the university, Meadows has had to make several adjustments.

“I think when I first started coming here, I was using one cane, then I switched to two canes, and then I switched to a rollator and I have a power chair,” she said.

Her power chair was featured as part of the Destroy the Gap art show in 2023. She transformed the chair into a train, which allowed her to pull several carts behind her, so she was able to move things more easily.

“I’m fairly independent and I don’t like having to ask for a lot of help to do things because, you know, I may be disabled, but that doesn’t make me completely unable to do things,” said Meadows.

She also said she has learned a lot about having to adapt, although, when she does need help, she asks for it.

“I do get help when I have something like a stump in my car and I ask the head of the art department, ‘Hey, can you help me get this out of my car because I was just going to shove it out with my feet,’” she said.

Another example of adapting to each situation is that she can no longer use a hammer to create her art, something that is important in what is known as repoussé chasing, which uses copper to create artwork.

Meadows said she appreciates when some professors know she may need adaptions. One instance she said was when her professor gave her a tray that had different hole sizes in it, which allowed her to hammer with only one hand to not vibrate her fingers.

“They called it carpal tunnel but it’s closer to tendonitis,” she said.

Though she is adjusting, it doesn’t mean she won’t do the work, it means that she’ll have to do it at a slower pace than usual.

Another type of art Meadows has been creating involves leftover metal. She said the students in metals classes tend to drop metal on the floor, so she picks up the little pieces and has been making people out of them.

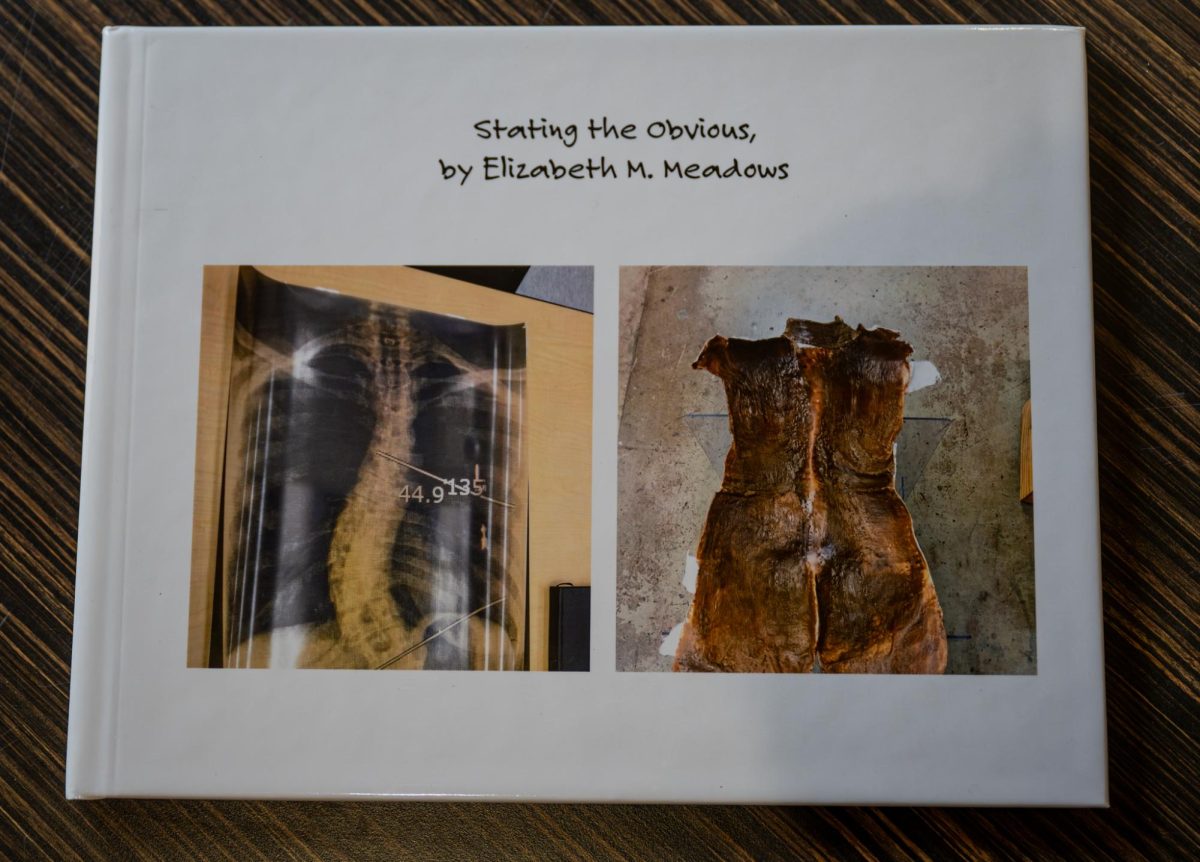

Something unique she creates is a representation of the disabilities and medical challenges she has.

“I actually cast all of my body parts that have medical issues, and that’s most of my body,” she said. “The only things I don’t have problems with are my thighs, my lower legs and my upper arms.”

In addition to all of this, she said her medical conditions have influenced her work. One condition she has had since she was younger is scoliosis, but it wasn’t caught until she was 16.

While having more conditions, she said she appreciates her rollator, which she’s been using for around two years, and received it as a birthday gift from her mom. Her powerchair is mainly used when she has flare-ups, one of which is a tailbone flair-up, as she has broken her tailbone several times.

Despite having made some of her own adaptations to attend school, she said there are issues she’s noticed with the university campus.

“The campus is not incredibly ADA-friendly. There aren’t enough parking spots close enough to all the buildings, the ADA doors don’t always work, there are classrooms that I cannot get to because there are staircases,” said Meadows.

Meadows recalled that there had been a few challenges she’d encountered.

“I have professors that ask me to climb stairs,” she said. “The art building is old, so there are loft spaces or graduate studio spaces upstairs, and people want me to go up there, and I’m like ‘yeah, do you have a dumbwaiter?’ If I had a dumbwaiter, I’d go up there, but I’m not doing that.”

Another issue Meadows said she encountered was getting stuck in the snow while using her power chair.

She said during one of the Symposium of Diversity events, she drove her powerchair from the art building to the Bowen Thompson Student Union but got stuck in the snow.

“I got stuck in the snow and I called someone over and they helped push me out of the snow, and then I had to figure out how to get into the building, so I had to drive completely around the building to get into the doors that would put me on the correct level of the student union,” said Meadows.

She said she obtained the assistance of another person to help get into the building but had some challenges doing so.

“I got stuck between the inside door and outside door, so he had to climb over me to open a door,” she said. “My powerchair is like a zero-turn powerchair, so I was able to turn and get my cart around and through the door, and then travel through the hallway, up the ramp, and turn the corner, and then I just burst into tears because I was like ‘this was hard.’”

She said she was told the new university buses have the ability to carry a powerchair or wheelchair, but she said the distance to the bus depot is almost as far as driving herself.

Though she has encountered some challenges, she said there is one example where she appreciated her professor’s effort.

She recalled taking voice classes in the music building and there being a time when the piano was on one level of the building which required stairs to access, but she got somewhat creative.

“Then finally I just said, ‘Can I be in the balcony and sing to you from up there? I’ll be Juliet and you can be Romeo,’ and that worked for a little while, and then she got a classroom that was more accessible,” said Meadows.

She said she is grateful for that professor’s willingness to work with her.

“I appreciated that because that really showed sensitivity to the fact that walking a rollator down a flight of stairs while you hold on for dear life to the handrail is dangerous,” said Meadows.

Meadows said she believes there’s a lot of work to be done in how society sees people with disabilities.

“The world is a voyeur to people with disabilities and I think they get some kind of sick satisfaction and maybe some feelings of superiority, ‘Oh, I’m not that bad. Oh, I’m not that disabled,’” said Meadows.

She said one recommendation is to help someone if they need help.

“There’s a lot of witnesses to events as opposed to people helping people who need help,” she said.

One example she provided encourages students to help their peers.

“Students need to be aware that if you’re sitting, looking out the window and you see a person in a powerchair, and they’re stuck in the snow, maybe somebody should come over and help the person,” said Meadows.

One reason she said she encounters challenges as a person with a disability is because of stereotypes.

“I think there’s just a lot of stigma about physical disabilities and there’s stigma about mental health disabilities,” she said.

She said it’s issues like stigmas that can cause other problems.

“I think a lot of people try to mask their disability so that they don’t have to deal with the stigma because people make jokes that aren’t funny,” she said. “I have heard some jokes that are tasteless, and I don’t have the energy to fight every person that is just ignorant—there’s a lot of ignorance.”

In addition, she said these assumptions are sad for the person making them, not her.

“People who don’t necessarily understand disability will make assumptions about a person and that’s sad—sad for them. More sad for them than it is for me because I’ll just tell them how rude it is,” said Meadows.

As for recommendations for the university, she said she thinks there’s some work to be done.

“I think that faculty needs to be retrained, administration needs to be retrained [and] they need to have more than Black Issues Conferences. They need to have a conference that’s just as large as the Black Issues Conference that’s about disability issues,” said Meadows.

In addition, she said she’d like to see the university being more open to feedback. Something she said, she hasn’t seen enough of.

“There’s questionnaires about so many things but there’s no questionaries, that I’ve seen, about how it is to be a disabled student on this campus,” said Meadows. “It’s rough, that’s what it is, very rough.”

She also said for people with disabilities, one of the most important aspects is asking people what their needs are.

“Ask people with disabilities, don’t make decisions without actually talking to disabled people. That’s got to be the most offensive thing that has happened since I’ve been here,” Meadows said when asked about what she thinks the university should do for people to have equal accessible access.

One other recommendation Meadows said the university could implement is involving BGSU students with disabilities to make sure things are still working how they should, such as ADA-accessible doors.

“You should have a volunteer that is disabled go all the way around campus and try every single door and then report it all—these doors work, these doors don’t work,” she said.

BG Falcon Media reached out to the university’s Accessibility Services, but they declined an interview and referred us to their website.

According to Accessibility Services’ webpage, “The mission of Accessibility Services at Bowling Green State University is to provide equal access and opportunity to qualified students, faculty and staff with disabilities. Our goal is to increase awareness of disability issues and support the success of students with disabilities by providing opportunities for full integration into the BGSU community.”

The website provides information in various areas ranging from applying for services, disability training, to filing a complaint, among many other topics.

To apply for services, students are required to submit documentation of their disability to be reviewed by the Accessibility Services staff. There are three things a student must do to request accommodations including submitting a Request for Accommodation Form, a Disability Verification Form, and the student’s most recent Individualized Education Plan (IEP), 504 plan or multi-factored evaluation (MFE).

The website also allows students, staff and faculty to request a 50-minute online training on disability etiquette, regulations, rights and responsibilities at BGSU and responding to public requests for accommodations.

In addition, the website provides the department’s complaint procedure and the written appeal process.

Jules Patalita is a Disability Rights Advocate at The Ability Center of Greater Toledo and provided insight into some of the concerns. Patalita is not an attorney, but an advocate who supports individuals with a disability.

He said in regard to accessible parking spaces, the spots should be on an accessible route.

“When we’re looking at those, the ADA standards want them to be on an accessible route—whatever the accessible route is, it needs to be on an accessible route from parking into whatever building or facility someone is trying to get to,” said Patalita.

In addition, he also said there’s no maximum distance specified, and there’s a small amount of wiggle room depending on where the route and entrance are located.

Further, he said if there are numerous parking lots, there needs to be accessible spots in each lot.

He also said accessible doors not working is something he hears very often.

“Looking at general complaints of someone saying that a location is not accessible for whatever reason—doorways and entrances and the actual hardware to get a door open—is one of the most common things we hear,” said Patalita. “Doors not being accessible, or the door handle itself or the way to open the door not being accessible, yes, we hear that very, very, very often.”

In a situation like Meadows’, he said it’s more about the individuals rather than the whole for who’s affected.

“I think it’s going to be less about the disabled community as a collective whole having an opinion and more that hundreds or thousands of people, individuals that make up that community. Each one will probably have their own reaction to the case,” said Patalita when asked about the university’s response.

In contrast, he also said he understands why the university may not have commented.

“I also understand, especially working for a government entity, I understand why the university’s place may be to stop and have an internal review, and approach the situation slowly and get all of their details in a row before they would want to go public,” said Patalita.

However, he said it’s important Meadows’ situation is being talked about.

“In situations like this with people speaking up, this is the exact way that progress has been made in any field, but especially in the field of disability access and disability rights,” he said. “I feel horrible for the student that had a case like this, but I’m really glad to see that they are going public and talking about it so that this can raise more awareness, and that hopefully, this can lead to situations like this happening less and less, until hopefully one day they never happen.”

Meadows said she’s encountered some challenges with her daughter’s school, as she also has a disability. From these experiences, Meadows has learned to advocate not only for herself and her daughter but for fellow BGSU students.

In addition, Meadows said if she requests something but doesn’t receive it, she advocates for her own needs, something that she wishes students knew they could do as well.

“If I asked for something and I can’t get what I need, then I escalate, and I just think that most students don’t understand that they have the power as humans to ask for assistance, and if you don’t receive the particular assistance you’re supposed to receive from the particular agencies or divisions that are supposed to give it to you, then you escalate,” said Meadows.

She said even when things become tough, she stands behind her decisions.

“The escalation process is ugly, and it makes you feel like—you don’t want to get somebody in trouble, and you don’t want to get somebody fired. They’re not going to get fired. What’s going to happen is there’s going to be a review and retraining but no one’s getting fired over this,” said Meadows.

Further, she said she’s advocated on behalf of students, which she thinks may have something to do with her experience being a mother.

“There’s a fear that you’ll get someone in trouble, so students don’t want to advocate for themselves, so they’ll tell me because I’m their mom’s age and then I’m advocating for them and I’m saying, ‘Hey what can we do? This person has this issue,’” said Meadows. “I’ve asked them to speak with administration, and you have to teach people how to advocate for themselves when they weren’t taught by their parents, or they just didn’t know that they would have to advocate.”

Meadows also said there is a large percentage of students who may be fearful of missing class when they need to.

“People who are shy, people who have anxiety disorders, people who have depression issues, people are terrified to miss classes because they’ll be marked absent,” said Meadows. “Well, if you’re having a crisis, you shouldn’t be marked absent, but there’s a process you have to go through, you have to notify people, and it’s embarrassing to have a mental health crisis or have a physical crisis.”

Though some may wonder why Meadows is so passionate and outspoken about these types of issues, she said she feels like she needs to be.

“I feel like I have been given an opportunity and a voice to speak up,” she said. “I don’t always have the self-esteem necessarily to feel like I’m that important, so I tend to talk to people the way I wish someone had spoken to me about these subjects.”

She said you simply have to stand up.

“I’m advocating for students who don’t understand what the process is—they don’t understand it,” said Meadows. “If you don’t speak up, your needs will be ignored, you have to speak up, you have to advocate for yourself, and you have to advocate for others.”

Lastly, she said it’s still important to advocate, even when it becomes uncomfortable.

“It’s uncomfortable, it makes you stand out, it makes you feel like a target, and it might actually make you a target,” said Meadows.

As she traveled the halls of the Fine Arts Center, she encountered smiles and “hellos” from dozens of both students and staff in the hallways.

However, as she used her rollator to enter a room where her work is stored, she was reminded that she oftentimes has to advocate for herself, too.

“I was expecting my work to be in a certain room, and I have not been at school recently for health reasons, and when I came in, my work was not in the room,” said Meadows. “So, we looked through the whole room and then I looked out the window and saw that my things had been thrown outside, and I’m saying thrown outside because they were not gently carried, they weren’t organized in the manner that they had previously been organized, which means delicate pieces are broken or may have gotten broken.”

Meadows said this experience was frustrating, and something she said, shouldn’t have happened.

“I was frustrated because communication is very helpful and if something needs to be moved within a certain period of time, everyone has my cell phone number and I didn’t receive a text that said, ‘Hey this is what’s going on, we need you to move your things within this period of time,’” she said

Meadows also said she’s aware that the room is a space used by multiple other people. However, she said communication shows concern for people who can’t always move things by themselves.

“Sure, I’m guessing that my things were moved harshly, but based on the fact the two bedframes were piled on top of my delicate pieces that are in progress means that the same attitude I’ve been dealing with the whole time has continued,” she said.

She said it still makes her angry that it even happened.

“It makes me very angry and it’s just a continuation of disregard for a person that has disabilities and not treating them with the same amount of respect that you would treat someone else,” said Meadows.

When asked about one thing Meadows wishes her fellow students should know, her response was simple: Hold the door.

She said it’s the smallest gesture that could make someone’s day.

“I do want to say that most of the students are actually very nice about holding doors if they notice me. If I ask for help, someone will usually give it, but look behind you when you walk through doors,” she said.

Even when you may not know it, she said it’s the action that counts.

“Sometimes there’s a person who’s disabled who might need a little help or a little time getting through that door. Sometimes you can just make someone’s day by holding a door,” said Meadows.

Your donation will support the student journalists of Bowling Green State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.